I am always looking for new resources regarding the use of restorative practices in the classroom and it seems over the past year or so there have been some really great guides and readings developed for educators.

Happy Reading –

I am always looking for new resources regarding the use of restorative practices in the classroom and it seems over the past year or so there have been some really great guides and readings developed for educators.

Happy Reading –

As evident from my previous post, I do not use the practices and structures of restorative justice in a traditional sense. I use the circle as a structure to my class or in a professional setting as a means of management, accountability and community building.

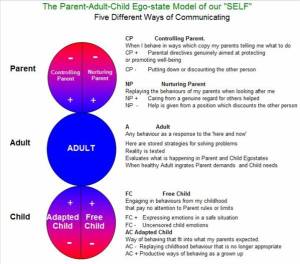

The restorative questions provide similar opportunities for teachers to manage student accountability and to build respect in the  classroom. Youth are uninterested in taking responsibility for their actions because they do not want to be punished. As a teacher, I am uninterested in being an authoritarian over my students. I don’t enjoy the parent/child relationship and prefer to empower my students to make positive and responsible choices as an equal to myself and everyone else in the class. When students understand there is no punishment they are far more open to taking responsibility for their actions and make things right again!

classroom. Youth are uninterested in taking responsibility for their actions because they do not want to be punished. As a teacher, I am uninterested in being an authoritarian over my students. I don’t enjoy the parent/child relationship and prefer to empower my students to make positive and responsible choices as an equal to myself and everyone else in the class. When students understand there is no punishment they are far more open to taking responsibility for their actions and make things right again!

For the skeptics out there, please keep in mind that there are some very important factors involved in facilitating these questions in any number of situations and environments.

1) Is the person who caused harm willing to participate? How willing are they to answer the questions?

2) Those involved must focus on the facts and be true to their own reality and experience of the incident. It is the responsibility of the facilitator to guide and reassure those participating that honest is not going to result in a punishment, but that we are all working together to restore things back to the way they were.

As a teacher, I find these questions not only help me resolve issues in the classroom but to also understand things about my students that help me to be proactive in the future concerning behaviour issues. When people first begin practicing restorative questioning, it can be difficult to imagine what the conversation is going to sound like. A few years ago, I came across an article posted by Julia Steiny that provides and excellent example how restorative questioning can be used in school and what the specific conversation would sound like…

http://www.educationnews.org/ednews_today/101258.html

A darling, cocky boy gets kicked out of class and into the suspension room. He has that goofy look of a kid who knows he’s been a jerk, but figures he’ll stonewall the adults by pleading innocence. We’ll call him Manny. He looks to be a young 14.

But instead of just parking him with other “bad” kids for a while, this school is starting to experiment with “restorative practices,” an alternative to traditional punishments like suspension. Research says suspension doesn’t work anyway, because it doesn’t teach social skills. I’m working with the school on “restoring” kids back to the community fold, by asking standard questions that help them think through their behavior. The questions are gold in my opinion. This story is a real-life image of how they can work.

The busy staff member bringing Manny in mentions only that he was yelling out the window. In itself, the offense sounds like something a teacher could handle on the spot, but we don’t know what else might have happened or how chronic this behavior has been.

The first Restorative Question is always: What happened?

Restorative practitioners focus on “what” and not “why.” “Why” invites a lot of useless reasoning and getting into other people’s heads and motives. Observable facts are important and push the kid toward an objective perspective.

Manny insists, “Nothing happened! I saw a friend of mine out the window, so I got up and said hey. Really, Miss! That’s all!” He starts to explain that the teacher was wrong, which kids do. So I cut him off, reminding him that we’re not here to talk about the teacher’s behavior, but his. He shrugs and nods. We move on.

I ask him to take me back a step and describe the scene leading up to yelling out the window.

Nothing was happening. He was in the back of the class chilling with his friends, like always, doing nothing.

Hmmm. I ask about schoolwork. What was he supposed to be doing?

“Oh, yeah, yeah, yeah,” he quickly remembers, “I was doing my schoolwork.”

I love kids. If they’re not yet hardened with antisocial defenses, they’ll just open their mouths and tell you what you need to know.

Okay, I say, you were in class with one eye on your work and another on your friends.

He smiles sheepishly, “Uh, yeah, something like that.”

And then you got up out of your seat and went to the window. “Yeah.” And what did you yell at your friend?

He rolls his eyes like it’s a stupid question and answers something to the effect, “Yo! Alex, up here! Whuzzup?”

I repeat back to him what is now a fairly clear scenario — with no editorial on my part, just the facts. He nods as I talk; I’m getting it. He thinks he’s off the hook. But when I get to him yelling out the window, I actually do yell, which makes him laugh. Still, he confirms my version of the story.

Next Restorative Question: Who else was affected?

“Absolutely no one!” Big surprise. They all say that, too.

Okay, Manny, pretend you’re not yourself, but another kid in the room, one of the ones in the front, doing their work. You’re yelling to Alex, and what happens to that kid?

Manny quickly uploads the image in his mind, and his face drops. He’s stepped out of his narcissism, and while looking back at his behavior he sees for himself what he’s done.

“We-ell. Just for one tiny second, I might glance up to see what was happening. But it would be only …” I cut short his efforts to minimize and ask how many kids were in the class. Probably, like, 20.

Okay, Manny, now pretend you’re the teacher.

Without hesitation he barks, “Okay, okay, I get it! I disrupted class!”

I thank him. Good! That’s honest.

The last Restorative Question I ask is: What would make this right?

This usually has a complex set of answers. The kid doesn’t want to be sent down here again, so we start with how he can avoid this particular hot water in the future. He thinks and umms, but concludes that he could sit in the front of the class, away from the window and away from his friends.

I ask if he really thinks he can commit to that. “Yeah, definitely.” I praise him for a very doable plan.

But, I point out, academic success is far easier when you have good relationships with teachers. Would an apology help? Whoa, no, that he can’t do. We talk a bit, but his heels are in the ground. I let go and count the incident as a big partial win. He’s gratifyingly pensive as I let him switch to doing homework.

Now, anyone, any mom, teacher, neighbor, or older kid could ask those Restorative Questions. Granted, it’s a bit of a skill not to react to the answers except with polite, clarifying questions, to keep the information flowing. But the point is to let the kid see himself in his own answers. Help him think.

Otherwise we’re just letting kids repeat their mistakes, over and over again.

By Julia Steiny

http://www.educationnews.org/ednews_today/101258.html

In my experiences, students do not learn to take responsibility for their actions from punitive consequences. They become defensive and put themselves in a victim role and often only learn not to get caught the next time. The restorative questions respect both the situation and experience of the person who causes harm and the person has experienced harm. It allows both parties to reflect on the events of the incident and express their part in it. The questions allow the person who caused harm to empathize with those who were harmed and to understand the impact of their actions. Collaboratively, all parties involved work together to make things right and allow everyone to move forward.

In every gathering, classroom or meeting space, I always have the people involved sit in a circle. I have facilitated circles as small as five people and as large as sixty people. I always find the reactions of the participants amusing when they learn we are sitting in a circle. My students often respond with comments that they are not kindergarten kids, adults often are reluctant and make witty comments about camp fires and sharing feelings. Regardless of age, everyone hesitates when finding a seat. In any setting where people gather, I find they will place themselves in the room based on their willingness to participate and their perceived importance within the gathering itself. For example, how many staff meetings have you been to where the majority of the people attending sit in the back of the room even though the front row of seats or the seats closest to the speaker are available to be sat in? Why does that happen? Are people uninterested in participating? Are they afraid of being asked to participate? Do they feel unworthy of being so close to the action?

When I work with youth, I often find myself telling them to make a choice and own it. Do something, don’t do something; it’s up to you because you have the power to make choices and own them. To me, if you are going to attend a gathering, a class, a meeting, whatever, then you should be there not just physically but also mentally. This is one reason why I sit everyone in a circle. There is no hiding away from what it is we are there to accomplish as a group. There is also no divide in power. Traditional classrooms have the teacher at the front of the room and the students sitting in rows facing the teacher; office meetings and workshops or lectures often function the same way. When sitting in around a long boardroom table, there is still a clear distinction of roles even though people are sitting in-the-round. This traditional setting does not allow for conversation or the inclusiveness that circles can provide. In a circle, there is no distinction between “teacher” and “student” roles. We are all equal and everyone placed the same distance from the center of the meeting as everyone else. In a circle, we can see each other and others can see us. In a circle there is no natural beginning or ending; it doesn’t matter where you sit in the circle. I think this equality scares people, because there are responsibilities to being part of a circle that do not necessarily exist in a traditional “teacher” and “student” setting. When you disappear into the density of people sitting in the back of the room, it is much easier to zone out, play on your cell phone or hold a separate conversation without facing the same social repercussions as you would if you engaged in those behaviours while sitting in a circle. When everyone is sitting in a circle they are forced to not just make the choice to be there both physically and mentally, but to own their chosen behaviour and understand that there are consequences for choosing to not fully participate. Jill Bolte speaks about her experiences with a stroke in a TED conference talk, where she explains the difference between how our right and left hemispheres of the brain function. The traditional “teacher” and “student” setting is, in my opinion, a left brained practice because we are individuals, who choose to participate as it suits our needs. The circle setting is, again in my opinion, a right brain practice because in the circle we are a community, accountable to each other and equal in relationships to one another.

As a drama teacher, I begin all of classes with a circle. The class begins with a check in, a simple exercise that creates community and empathy among students. I also conduct lessons in circles because they allow for open discussion and shared learning.

As a program facilitator, I have had to co-organize an orientation night with the purpose of introducing new students to the function and purpose of our program. Sixty students, parents and facilitators sat in a large circle and participated in community building games which took place in the center of our large circle.

I have facilitated a staff meeting with fifty teachers sitting in a large circle. We discussed the uses of restorative practices in the classroom and the conversation allowed for a variety of opinions and ideas on education and teacher/student relationships.

This is a picture of me teaching a drama class to thirty kindergarten students at an inner city school in Mississauga. To some, the idea of engaging thirty 4-6 year olds in drama games would be hell on earth.

In the circle, the students were easy to manage and everyone was involved. The teachers commented on how open and willing some of their more shy and quiet students were in the circle setting. They also commented on how shy some of their more lively students became in the larger circle. Interesting…